On a slushy Saturday morning in mid-February, hundreds of Louisvillians stand outside Roosevelt Perry Elementary School on West Broadway, the line wrapping around the building and snaking into the

POSTED ON: 9 MAR 2018 – 3:57PM

On a slushy Saturday morning in mid-February, hundreds of Louisvillians stand outside Roosevelt Perry Elementary School on West Broadway, the line wrapping around the building and snaking into the parking lot. They bundle themselves against the cold.

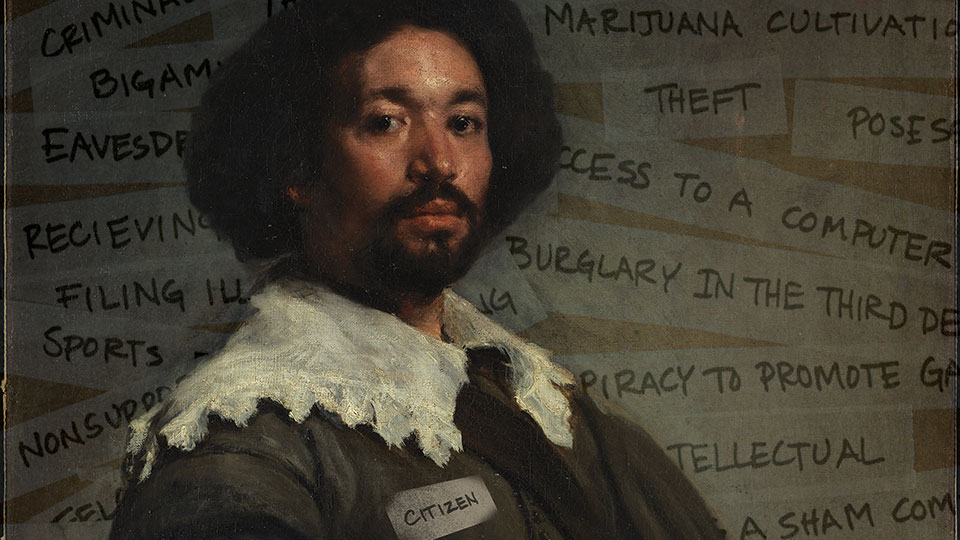

They’re all here for the pilot clinic of the Reily Reentry Project, a program through the Louisville Urban League designed to help people expunge their criminal records. It’s named for Urban League board member and Speed Art Museum director Stephen Reily, who donated $300,000 to fund the program for three years. The program covers most, if not all, expungement costs; participants are then required to enroll in an Urban League program, on topics such as health or housing. Reily became interested in the issue while walking the Highlands, campaigning for his ultimately unsuccessful 2016 Metro Council run. He says he met would-be constituents who were invested in the race but couldn’t vote due to felony charges from years or decades ago. Reily was shocked upon realizing the lingering effects criminal records have on the city’s workforce, neighborhoods and families. “Louisville can’t succeed unless everyone can,” Reily says. “Our city’s deepest internal problems result from a history of legalized segregation that has concentrated poverty in certain specific neighborhoods. And in those neighborhoods, too many people are denied access to good-paying jobs, or even the right to rent an apartment or buy a home, because they have a criminal record — even long after they have served their time and paid their debt to society.”

A door that had been shut to former felons cracked open in July 2016 with the passage of Kentucky House Bill 40, making those who had committed a Class D felony — more than 50 offenses, from possession of a controlled substance to third-degree burglary to sports bribery — eligible to have their records expunged five years after completing their sentence or parole. Applicants must obtain a certificate of expungement for $40 before paying the $500 to file for the expungement itself. Reily says these financial requirements put the opportunity out of reach for those who need it most. His project aims to combat this issue with 40 attorneys from the local firm Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs, who have volunteered their services to help participants through the expungement process.

At Roosevelt Perry, the attorneys face their clients across student desks that line the halls and fill the library, walking applicants through the paperwork necessary to start a process that can take months to complete.

Among those helped at the clinic is G.V. Searcy, who exits the glass double doors of the school feeling like a new man. He spent about four hours waiting for his turn in front of an attorney. “You just feel lighter, like a weight is off your shoulders,” Searcy says.

The clinic is intended to run from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but is forced to close early because it reaches capacity after admitting about 500 people. At about 11 a.m., organizers tell those still waiting outside that they can stay, with no guarantee of getting to see an attorney. Some have been waiting since 8 a.m., including 66-year-old Barbara Petty. She says she was arrested on charges that were later dismissed but that the mark on her record still hangs over her head. She must now wait until a future clinic to begin the expungement process. “It’s been hard to find a job, to find good housing,” she says.

Louisville Urban League president and CEO Sadiqa Reynolds, who is on-hand to assist with the clinic, says that turning folks away is hard to do. The overwhelming turnout has Reily and Reynolds discussing the possibility of expanding the funding. Ultimately, the Urban League hopes the data from the clinic will persuade the state legislature to make expungements more accessible. “The funding is for $100,000 a year, and we’re going to do it until the money is gone,” Reynolds says.

Around lunchtime, Reily steps out and returns with 75 pizzas to feed the crowd. He mentions that hundreds of people are getting a second chance today — and that there are so many more to help. “When hundreds — maybe thousands — gain access to good-paying jobs, they can start to lift their families, their households and their neighborhoods out of poverty,” Reily says. “This may be the best way to start breaking the cycles of concentrated poverty that have trapped too many families and neighborhoods in Louisville for decades.”

This originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of Louisville Magazine. Every story in our March issue is about west Louisville, and we’ve barely scratched the surface. Click here to read more from part four of our series on the West End.